Piano Blog by Skoove – Piano Practice Tips

The whole tone scale is a surreal and enigmatic sound that often feels ambiguous and unanchored. The scale is perfect for creating dream-like passages and is commonly found in the work of Impressionistic composers like Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. However, examples of the scale date back to the 17th century.

The whole tone scale offers an interesting palette of colors and textures to explore with a very distinctive sound that is quite different from the traditional diatonic scales. Learning to use these sounds will expand your ears and open your fingers to new and interesting sound worlds.

In this article, we will learn the construction of the whole tone scale, explore the two variations of it, and learn the chords associated with it. When you are ready, dive in!

What is the whole tone scale?

The whole tone scale is quite literally a scale built in a series of whole steps. It is one of the most straightforward musical ideas. If you feel like you need some refreshment on basic scales and chords, consider trying some online piano lessons.

How many notes are in a whole tone scale?

The whole tone scale consists of six notes and is therefore called a hexatonic scale. However, there are many possible six note piano scales, so musicians primarily refer to this set of pitches specifically as the whole tone scale.

The whole tone scale also consists of half the notes from the chromatic scale.

How to build the whole tone scale

Since the whole tone scale is built in in a series of whole steps, it is rather easy to construct, both visually on the piano and on paper. There are two variations on the whole tone scale. Let’s walk through them both together.

The C whole tone scale

Starting from middle C, count up one whole step to D. One whole step above D is E. One whole step above E if F♯. One whole step above F♯ is G♯. One whole step above G♯ is A♯. One whole step above A♯ returns us back to C, one octave higher than we began.

This means the C whole tone scale is spelled:

C – D – E – F♯ – G♯ – A♯ – C

Not too complicated, right? Check it out notated for the piano below:

Of course, we could also notate the scale with the sharp notes written as enharmonically equivalent flat notes like this:

The D♭ whole tone scale

The second variation on the whole tone scale begins on D♭. It follows the same pattern of a series of whole steps.

From D♭, skip up a whole step to E♭. One whole step above E♭ is F. One whole step above F is G. One whole step above G is A. One whole step above A is B. And finally, one whole step above B is D♭.

This means the D♭ whole tone scale is spelled:

D♭ – E♭ – F – G – A – B – D♭

It looks like this notated on the piano:

If you want to think in terms of scale degrees, the formula for the whole tone scale would be:

1 – 2 – 3 – ♯4/♭5 – ♯5/♭6 – ♯6/♭7

There is some ambiguity in this situation. It is not common to see a sharp sixth scale degree. However, if you notate the pitch as A♯, that is technically the sharp sixth of C. This is one instance where there is some malleability in music theory.

Why are there only two whole tone scales?

The whole tone scale is a symmetrical scale. This means that you can start from any tone in the scale and the scale will consist of all of the same pitches.

Think about it for a minute. The C whole tone scale is spelled C – D – E – F♯ – G♯ – A♯ – C. If we begin the scale from D, then the scale will be spelled D – E – F♯ – G♯ – A♯ – C – D. While we have a different root, the pitches of the scale are exactly the same. This holds true if we begin from any of the six tones in the whole tone scale.

If we cover six pitches in one scale, then it is only logical that we cover the remaining six pitches in the second scale. The D♭ whole tone scale is spelled D♭ – E♭ – F – G – A – B – D♭. If we start from E♭, the scale will be spelled E♭ – F – G – A – B – D♭ – E♭.

Compared to diatonic scales

This differs from the concept of the modes in the diatonic scales. For example, if we take the C major scale (C – D – E – F – G – A – B – C) and begin from D, we have the D Dorian mode (D – E – F – G – A – B – C). While this scale has the same tones as the C major scale, it has a completely different intervallic pattern, which gives the scale an entirely different character than the C major scale.

Likewise, the whole tone scale does not produce a definitive tonic to dominant cadence like the diatonic scales or harmonic minor scales do. Consequently, the root of the scale is malleable and more dependent on musical gesture and expression for resolution than a strict harmonic motion.

The chords of the whole tone scale

Another way to view the whole tone is scale is the combination of two augmented triads a whole step apart. Remember that the augmented triad is a three note chord built from two major thirds. So, the C whole tone scale is the combination of a C augmented triad (C – E – G♯) and a D augmented triad (D – F♯ – A♯).

If we put these notes in alphabetical order from C, we find C – D – E – F♯ – G♯ – A♯, the notes of the C whole tone scale. Additionally, it is important to remember that augmented triads, like diminished triads from the diminished scale, are symmetrical chords.

Triads of the whole tone scale

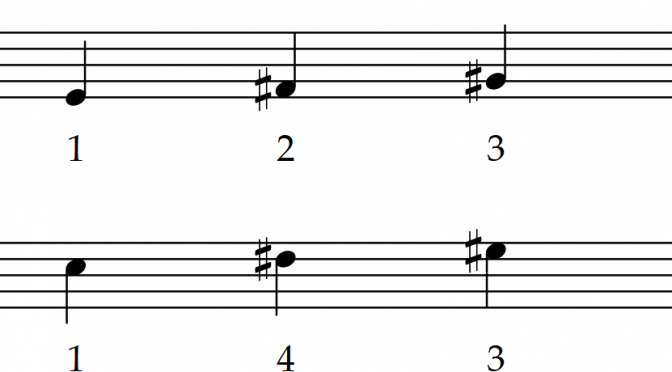

Let’s use the process of stacking thirds to build the piano chords of the C whole tone scale. Remember, all you need to do is alternate every other note in the scale to build these chords. Check them out notated below:

Obviously, nobody likes to look at the spelling of F#, G#, or A# augmented. Double sharps are no fun to read. But, what can you discern about the nature of the scale from these triads?

The most important thing to realize is that every triad built in this scale is an augmented triad. This makes sense because the scale is built from the combination of two augmented triads a half-step apart and augmented triads are symmetrical.

Using the whole tone scale

The whole tone scale is primarily used in improvisation over augmented triads and seventh chords. These chords happen primarily in jazz compositions, so if you are interested in learning about jazz music, then you should learn the whole tone scale.

Here is an exercise you can practice to develop your facility for improvisation within the whole tone scale:

Famous examples of whole tone scales

There are many great examples of whole tone scales found in music across genres. The classical music of Claude Debussy is full of examples of the whole tone scale. For example, his piece “Voiles” opens with a descending passage of thirds inside the whole tone scale.

The Stevie Wonder tune “You Are The Sunshine of My Life” features a classic example of the whole tone scale in the song’s introduction.

Numerous examples of the whole tone scale exist in jazz repertoire as well. Tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter’s composition “Juju” is a great example of the whole tone scale.

Summing up the whole tone scale

The whole tone scale is an intriguing and ethereal sound. It is a symmetrical scale constructed from a repeating pattern of whole steps. It is also the combination of two augmented triads a major second apart. The whole tone scale consists of six notes and all the triads built from those six notes form augmented chords. The scale basically consists of that one sound.

If you are interested in learning more about different scales and other music theory topics like chords and intervals, or are simply looking for a fun and effective way to learn piano, Skoove offers lessons for every interest. With over 400 lessons ranging from beginner to advanced and a growing online library of articles on a wide range of topics, Skoove will help you open new doors to the wide universe of music. Try it out today!

Author of this blog post:

Eddie Bond is a multi-instrumentalist performer, composer, and music instructor currently based in Seattle, Washington USA. He has performed extensively in the US, Canada, Argentina, and China, released over 40 albums, and has over a decade experience working with music students of all ages and ability levels.

Read More

This article is from an external source and may contain external links not controlled by Empeda Music.