Piano Blog by Skoove – Piano Practice Tips

Music key signatures are an important tool to unlock the secrets of written music. Key signatures serve a few important functions. They serve as a sort of shorthand method for notating sharps and flats. By using a key, we do not need to notate a flat or sharp symbol everytime one occurs. If we have a melody with many F♯ notes in it, we can use the key signature with F♯ in it and save ourselves the hassle.

Key signatures also clue us in to the key of the song, or the main set of pitches that will be used. If you see a key signature with a single F♯, you can bet that the key will be G major or E minor, as those are the two signatures with an F♯.

All of this may seem a little confusing at this point, but there is an easily understood system behind all of it.

What are key signatures?

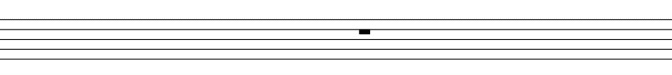

A key signature is a collection of sharp (♯) and flat (♭) symbols that sits between the clef and the time signature in a piece of music. Here is an example of a key signature with a sharp in it. Pay attention to the location of the key on the staff:

This particular key belongs to the keys of G major and E minor. Each key has a major and minor component connected by the concept of relative major/relative minor. However, for the rest of this post, we will focus only on the major key signatures and not the minor key signatures.

Basically think about it like this: if you see a piece of music with an F♯ in the key, that means that all the F notes in the song will be sharp, unless they are marked with the natural (♮) symbol.

Same thing goes for a key signature with a flat. Here is an example of a key with a flat:

If you see a key, like the one above, with a B♭ in it, that means every B note will be flat, unless it is marked with the natural symbol. Of course, the song may have more flats or sharps in it, but those will all be marked. Sharps and flats not marked in the key signature are called accidentals.

How to remember key signatures

Notice how the key signature with the flat sits in a different position on the staff than the sharp? This is because there is a progressive order to the keys.

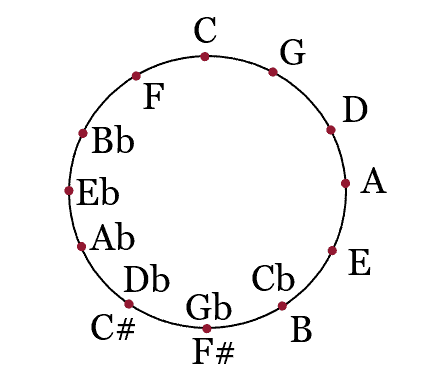

The order of keys follows the circle of fifths. The circle of fifths is sort of like a musical color wheel. It is a useful tool that organizes all 12 pitches around a circle so that each pitch is a perfect fifth apart. Check out this diagram below of the full circle and check out the linked article above if you are unfamiliar with the concept:

It is easiest at the beginning to think of the circle of fifths like a clock. So, starting at the 12 o’clock position, we find C. The circle of fifths also serves as a logical key signatures chart. The key of C major has zero sharps and zero flats. If you see a key with zero sharps and zero flats, you can be reasonably sure that the piece of music is in the key of C major.

When we move clockwise around the circle, we add sharps to the key. For example, the key of G major has one sharp, F♯, which we learned a moment ago. The key of D major has two sharps, F♯ and C♯:

The key of A major has three sharps: F♯, C♯, and G♯:

The key of E major has four sharps: F♯, C♯, G♯, and D♯:

Are you beginning to see a pattern? Each key moving clockwise adds one sharp to the key signature. The sharp that is added is a perfect fifth above the previous sharp. You can also think that the sharp that is added to the key is two spaces clockwise from the new key. For example, the new sharp added to the key of E major is D♯ and D is two spaces clockwise from E. Cool, right? There are many hidden secrets of music to be found on the circle of fifths.

We move clockwise around the circle until we reach the key of C♯ major. The key of C♯ major has 7 sharps: F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, and B♯. Notice how this entire pattern mirrors the progression of notes around the circle.

All 7 pitches in the C♯ major scale are sharp. If we continued to operate in sharp keys, we would need to start incorporating double sharps, which is a more advanced topic. For this reason, we call upon our knowledge of enharmonic equivalents to rewrite the sharps keys as flat keys.

Starting back at B, we can re-notate this as C♭, as you can see on the circle of fifths diagram above. The key of C♭ has 7 flats: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, and F♭. Notice how this pattern also mirrors the progression of notes around the circle, this time moving in a counterclockwise direction. Also notice how the key of C natural has zero sharps and zero flats, the key of C♭ has all 7 flats and the key of C♯ has all 7 sharps. Crazy, right? Here is the key signature of C♭ major:

If we continue moving counterclockwise, we find the key of G♭ major contains six flats: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭. The key of D♭ major has five flats: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭. The key of A♭ major has four flats: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭. The key of E♭ major has three flats: B♭, E♭, and A♭. The key of B♭ has two flats: B♭ and E♭. And finally the key of F major has one flat, B♭. Wow!

The circle of fifths is a useful visual tool to learn the progression of keys, but some students may prefer a key signature chart. This chart displays all the information contained on the circle in an easy-to-understand table. On the sharp page, each row descending lists the major and minor key center and the sharps added to the key. The flat page follows suit. Check it out!

How to read key signatures

Now that you understand some basics about what key signatures are and their progression around the circle of fifths, let’s practice using key signatures in some music.

Take a look at this short melody notated below without a key signature:

How many sharps do you see in this melody? In this melody, we have C♯, F♯, and G♯. Without a key signature, we have to write each sharp every time that it occurs. In more complex music, this can become very tedious and difficult to read.

Can you re-write this melody for yourself using a key signature instead? Which key contains three sharps? The key of A major contains three sharps. Here is how we would notate this melody using the key of A major:

Notice how much simpler this music looks than the first example. There are no sharps written on the music, all the sharps are notated in the key signature.

Additionally, once you feel comfortable reading keys, you could take one look at this and know instantly this melody is in the key of A major. This gives you a huge advantage for reading music because you already know which notes are going to be included in the melody and which notes will not be.

Let’s try another example with a flat key this time. Check out the short melody below notated without a key signature:

This melody has two flats notated in it, B♭ and E♭. Notice how both notes need to be notated twice because they occur twice. While this is a more simple example, in more complex music with denser chords and two clefs, this can become challenging to read.

Try now to re-notated this melody for yourself using a key signature. Which of the keys has two flats? The key of B♭ major has two flats, B♭ and E♭. Here is the same melody notated in the key of B♭ major:

This example is much more elegant and easy to look at.

Here is another handy trick for remembering the flat keys: the root of the key is always the second to last flat in the key signature. For example, in the melody above, the key is B♭ major. B♭ is the second to last flat in the key signature (it is also the first). Can you use that same logic to determine this key?

What flat is second to last in the above key signature? The flat symbol is on the second line and G is the note on the second line of treble clef, which means that key signature marks G♭ major!

Changing keys?

Have you ever noticed a sudden up or down turn in a piece of music? Chances are what you noticed, especially in a pop song, was a change of key. Changing keys is an effective way to create a surprise in a piece of music. Usually, you won’t need to change any structural elements of a melody, you will just need to adjust the key signature up or down, generally by one half step.

So if you have a melody in the key of C major, and you want to create a feeling of uplight, you might shift the key up one half step to D♭ major. Check out this example below:

Notice here how the new key signature of D♭ major appears at the end of the first line, which gives you a big clue when you are reading to get prepared! Practicing changing keys like this is also a great exercise to develop your piano technique!

You can achieve a similar effect by shifting keys down a half step. This move gives your melody a feeling of descent instead of uplift. This example begins in the key of E♭ major and shifts down one half step to the key of D major:

Conclusion

Key signatures are an extremely useful tool to understand and utilize in your music making. You can use them to simplify your writing process and to unlock doors to reading and understanding music on a deeper level. Pay attention as you move forward to what keys your songs are in, the sharps and flats that exist in the scales and arpeggios you are practicing.

Additionally, if you are starting beginner piano lessons with Skoove, be sure to check out all the great lessons on music theory and piano technique and try to identify the key signatures of the repertoire you are practicing. Skoove makes it easy and fun to learn the deeper aspects of music while simultaneously learning music you love and enjoy playing.

Try out your free trial of Skoove today!

Author of this blog post

Eddie Bond is a multi-instrumentalist performer, composer, and music instructor currently based in Seattle, Washington USA. He has performed extensively in the US, Canada, Argentina, and China, released over 40 albums, and has over a decade experience working with music students of all ages and ability levels.

Read More

This article is from an external source and may contain external links not controlled by Empeda Music.