Piano Blog by Skoove – Piano Practice Tips

Rhythm is all around us. We can find it in every corner of the universe. Your breathing moves in a rhythmic pattern, sometimes faster and sometimes slower. Your heart beats in a rhythmic pulse. You walk at various speeds, eat at different hours, and mark the passage of time throughout the days and years of life.

Musical rhythm operates in similar ways. Learning the fundamentals of rhythm in music is crucial if you want to understand music theory at a deep and profound level. Fortunately, it is not that complicated!

What is rhythm in music?

All sounds have a duration. Every sound has a beginning point and an ending point. The combination of different durations of time and the intricate ways in which they interact with each other forms the basis of rhythm in western music. If you feel like you need to review some musical rhythms, then perhaps online piano lessons with Skoove are a great choice for you!

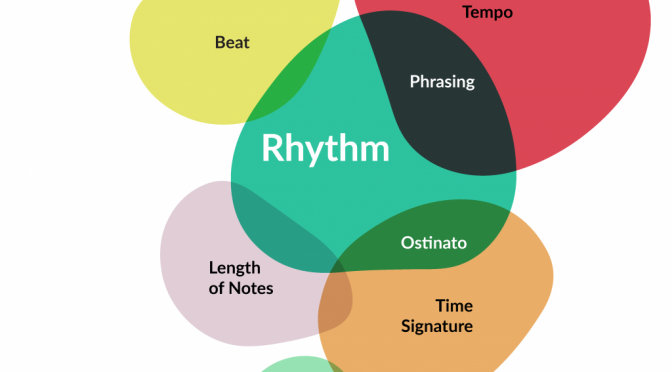

Types of rhythm in music

In a piece of music, there are a handful of basic durations you need to understand and master to improve your sense of rhythm in music. These are the tools musicians use when we speak of how to describe rhythm in music. We use notes to mark pitches and rest symbols to mark silence.

Longer durations

Both sound and silence in music exist across a duration. Let’s explore some durations of sound in music.

The whole note is the longest note value commonly used in musical notation. The whole note looks like this:

The whole note lasts for four counts or beats. Musicians will use the words counts and beats interchangeably, but they both refer to the duration of a particular note.

In musical rhythm practice, the first beat always occurs simultaneously with the first sound that you make. So if you play a whole note, count number 1 occurs at the same time you clap your hands. This is an important piece of information to remember.

The half note is a duration of two counts. It looks like this:

Shorter durations

The quarter note is a duration of one count. It looks like this:

Eighth notes last for a duration of ½ of a count. This means that it takes two eighth notes to equal one quarter note, four eighth notes to equal one half note, and eight eighth notes to equal one whole note.

Eighth notes come in two main forms: single eighth notes and beamed eighth notes. A single eighth note looks like this:

Two eighth notes beamed together look like this:

Sixteenth notes are the smallest commonly used note value. Sixteenth notes last for ¼ of a count. This means it takes two sixteenth notes to equal one eighth note, four sixteenth notes to equal one quarter note, eight sixteenth notes to equal one half note and sixteen sixteenth notes to equal one whole note.

Like eighth notes, sixteenth notes can be shown either as single notes or as notes connected with a beam. A single sixteenth note looks like this:

Four sixteenth notes beamed together look like this:

Subdivisions and more counting

Eighth notes and sixteenth notes belong to a category of rhythm in music that musicians call subdivisions. Subdivisions are a type of rhythm in music that are smaller than one beat.

In order to account for the additional rhythms inside of the beat, we need to add some more symbols.

To count eighth notes, we use a combination of numbers and the ‘+’ symbol pronounced ‘and.’ Here is an example of counting through eighth notes using the + symbol:

In order to play this sort of rhythm in music, clap the notes and speak “one and two and three and four and.” Congratulations, you have just counted through eighth notes!

Since sixteenth notes are twice as fast as eighth notes, we will need to add some more symbols again to account for the extra rhythms. We use the letters ‘e’ and ‘a’ pronounced ‘ee’ and ‘uh’ to count sixteenth notes.

Here is an example of counting through sixteenth notes using the +, e, and a symbols:

In order to play this type of rhythm in music, clap the notes and say “1 ee and uh 2 ee and uh 3 ee and uh 4 ee and uh.” Nice work! You have now counted through a group of sixteenth notes. Notice any feeling you may have of strong and weak beats in your sense of rhythm.

Do you see how the ‘e’ and ‘a’ symbols fit around the ‘1 +’ symbols used for eighth notes? Compare these two rhythms vertically:

As deep as you want to go

Eighth and sixteenth notes are two of the most common subdivisions you will find in music. You may have noticed a pattern in all of these rhythms. Each subsequent rhythmic pattern includes twice as many notes as the previous rhythm. Two half notes equal one whole note, two quarter notes equal one half note, two eighth notes equal one quarter note, two sixteenth notes equal one eighth note, etc.

We can extend this logic as deep as we want it to go. All we need to do is continue multiplying by two. After sixteenth notes, we can reach 32nd notes, then 64th notes, even up to 128th notes. These rhythms, especially 128th notes, are fairly rare. But, you will occasionally hear them in music at slower speeds where the instrumentalists can play extraordinarily fast. Additionally, all of these rhythms occur independently of dynamics in music.

Dotted Notes

You may have noticed that we have not explored rhythms with a value of three beats. In order to create a rhythm that lasts for three beats, we need to incorporate a new symbol: the dot.

If you see a small dot to the lower right hand side of a note, it has a special significance. The dot adds ½ of the original note value to the note. For example, if you see a dotted half note like this:

It means you need to do a little math …

The half note lasts for two counts. ½ of 2 equals 1. 2 + 1 = 3. This means that the dotted half note is equal to three counts. Make sense?

We can use a dot next to any rhythm to extend the duration of that note. Using this logic, what do you think the duration of a dotted quarter note is?

A quarter note lasts for 1 count. ½ of 1 is ½. 1 + ½ is equal to 1 ½. This means that a dotted quarter note is equal to 1 ½ counts, or the same thing as three eighth notes.

This makes sense when you consider the multiplicative nature of these rhythms. A dotted half note is equal to three counts, or the same thing as three quarter notes. A dotted quarter note is equal to 1 ½ counts, or the same thing as three eighth notes. Following, this means that a dotted eighth note is equal to three, sixteenth notes. Cool, right?

The possible dotted rhythms

There are many possible dotted rhythms in music theory. Let’s explore a few of them here, starting with the longest durations moving to the shortest.

Dotted whole note

The dotted whole note looks like this:

The dotted whole note lasts for six beats. Therefore, you won’t see a dotted whole note unless you have a time signature of six or more beats per measure. Otherwise, you will simply see a whole note tied to a half note.

Dotted half note

The dotted half note lasts for 3 beats. The dotted half note looks like this:

Dotted quarter note

The dotted quarter note looks like this:

The dotted quarter note lasts for 1 ½ counts, or the combination of three 1/8 notes. A string of dotted quarter notes looks like this:

Like the dotted quarter note hemiola, the dotted eighth note hemiola takes three complete measures to resolve in a 4/4 time signature.

Dotted sixteenth notes

The final dotted rhythm we will investigate here is the dotted sixteenth note. The dotted sixteenth note looks like this:

The dotted sixteenth note lasts for ⅜ counts, or the combination of three, 32nd notes. That is a small period of time! You will most often see this type of rhythm during fast passages at slow tempos.

Combinations of dotted rhythms

Dotted rhythms can be combined in many different ways. Most frequently, you will see chains of dotted quarter notes like we witnessed previously. However, you can see combinations of dotted eighth and sixteenth notes like this:

Here is a combination of dotted half, quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes in a melody:

Beams and partial beams

We have discussed a little about how subdivisions are beamed together. Let’s explore this a little further. Here is an example of how single and beamed eighth notes can appear simultaneously in music, with some counting included:

Sometimes in a measure, we have a combination of eighth and sixteenth notes that requires us to use a partial beam, or a combination of a single beam for an eighth note and a double beam for sixteenth notes.

Check out this example, with some counting included so you can clap through the rhythm yourself:

In this example, we have a combination of eighth and sixteenth notes forming some syncopated rhythms. We start with a single eighth note beamed together with two sixteenth notes. Then, we see a sixteenth note connected to an eighth note, followed by another sixteenth note. After that, we see the reverse of our first rhythm; two sixteenth notes beamed together, followed by an eighth note. Finally, we get an example of a single sixteenth note with a partial beam connected to a dotted eighth note. Don’t worry if you don’t understand all of that right now!

More on the threes

We have so far explored a few common rhythms where we split time into parts divisible by two. But, what do we do if we want to divide time into groups of three?

For example, what if we want three notes inside of one beat, instead of two (1/8th notes) or four (1/16th notes).

We use a rhythm called triplets to divide time into groups of three. At the start, it is important to recognize that triplets are not the same thing as three beats. Many students make the mistake of calling three eighth notes played together triplets. This is not the case. Triplets are their own, unique beast with a special feeling and nature.

Longer triplets

Half note triplets

Let’s explore two examples of “long” triplets i.e. triplets that stretch over 2 or 4 beats. For example, if we want to play three notes in the space of four beats, we would use a rhythm called a half note triplet.

Check out this diagram of a half-note triplet compared to a quarter note:

This rhythm exists between the half note and the whole note. We will explore a larger chart shortly where all of these triplets rhythms are shown in comparison to the previous rhythms we explored.

Quarter note triplets

If we want to play three notes in the space of two beats, we will use a rhythm called a quarter note triplet. Quarter note triplets look like this compared to quarter notes:

Shorter subdivisions

Eighth note triplets

If you want to play an even three notes inside of one beat, you will use eighth note triplets. The eighth note triplet looks like this compared to the quarter note:

The crucial part is the even nature of these notes. You can play three notes inside of one beat with a combination of eighth and sixteenth notes, as we have seen previously.

However, those combined rhythms do not produce three even notes inside of one beat; they are off-center. Eighth note triplets are three even notes inside of one beat.

Sixteenth note triplets

Finally, just as we have eighth and sixteenth notes, so too do we have sixteenth-note triplets, or sextuplets. Sixteenth note triplets are twice as fast as eighth note triplets and look like this compared to quarter notes:

While these might look like more complex rhythms, they are not that complicated. It primarily depends on the tempo or the number of beats per minute of the piece of music. Sixteenth note triplets played in a song at a slow tempo marking are actually quite simple, while quarter notes played at a faster speed can actually be quite difficult to feel properly.

Time signatures: how rhythm is organized in music

Now that you have some understanding of the different possible rhythms we use in music, it is important to learn how to organize these rhythmic elements into coherent musical forms. Musicians use tools called time signatures and measures to organize rhythms into understandable phrases with strong and weak beats.

It’s a combination of symbols that informs the musicians of three important facts:

The number of beats per measure of music.

Which type of rhythm will be the basic unit of time i.e. which type of rhythm will receive one count

Whether the piece of music will be felt in duple meter, triple meter, or quadruple meter or simple or compound time

One measure is the basic building block of musical notation. Measures are essentially rectangular blocks that are marked by vertical lines called measure lines or bar lines and define the rhythmic structure of music.

Simple vs compound time

We can further organize time signatures into two categories: simple and compound. Simple time is used for rhythms that can be divided into groups of two. For example, 4/4 and 3/4 are both simple time signatures.

On the other hand, compound time is used for rhythms that can be divided into groups of three. For example,6/8 and 12/8 are both examples of compound time signatures.

Simple and compound time can either be in duple and triple or quadruple meter. For example, 4/4 time is an example of simple quadruple meter because the strong beats are grouped in patterns of two (simple) and there are four pulses in a measure (quadruple). 6/8 time is an example of compound duple because the notes are accented in groups of three (compound) and there are two big accents in a measure (duple).

Conclusion

Rhythms form the foundation of music. Understanding the basics of counting music rhythm, feeling pulse, and understanding the pattern of strong and weak beats in time signatures will help you to become a better musician instantly.

Of course, you can practice all of this and more with Skoove whenever you want. Skoove is a great choice for learning piano online. With Skoove, you can learn all about music theory, rhythms, and songs anywhere you have a piano to play with. So whether you want to practice some syncopation with Fats Waller or get up to speed on your Beatles tunes, Skoove is a great tool to make your music dreams come true!

Author of this blog post:

Eddie Bond is a multi-instrumentalist performer, composer, and music instructor currently based in Seattle, Washington USA. He has performed extensively in the US, Canada, Argentina, and China, released over 40 albums, and has over a decade experience working with music students of all ages and ability levels.

Read More

This article is from an external source and may contain external links not controlled by Empeda Music.